It's been some time since I've wanted to write more than a "status update." But watching friends from my clubs--Larchmont Yacht Club and Storm Trysail Club--move from the idea of sailing their own boats in the 2017 Rolex Sydney Hobart Race to actually racing in it has inspired me to think more reflectively about how I am to accomplish my own sailing goals, which, at least right now, do not involve shipping my boat across the globe. Indeed, the way some like Chris Sheehan and Andrew Weiss have grabbed the horns of the bull we call adventure and wrestled it to the ground should inspire us all to think about how we transition from sailing dream to logistical reality. What do we want to accomplish over the winter, during the next sailing season, over the next five years? Do we want to improve our performance in local club racing, cross an ocean, cruise to unfamiliar anchorages? What do we need to do to make these goals a reality? These are some of questions I've been contemplating over the past few months, and more recently as I've been feverishly refreshing the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race tracker.

WINTER

As some of you know, I recently acquired a J/120--hull no. 38, ex-Eagle, winner of the 2009 J/120 North American Championships and 2016 NYYC Annual Regatta (PHRF 1), among other regattas. She is currently riding out the northeast winter at International Marine in Bristol, RI, where she traveled in late-October so that the Ocean State experts could diagnose whether she needed a below-the-waterline laminate repair. Although no major structural work is needed (phew!), she does need a few repairs and upgrades to prepare her for the next stage of her life, which I hope will include many ocean miles and opportunities for me to reunite with old friend, Jason Sudekis. Here's what's the on the winter punch list:

- Install second reef point in North 3DI main: Complete!

- Rebed the cabintop handrails, salon handrails, and genoa tracks.

- Replace and rebed the forward Lewmar hatch.

- Replace bilge pump and bilge plumbing.

- Replace starboard holding tank with water tank, and install new holding tank in v-berth.

- Potentially replace black water plumbing.

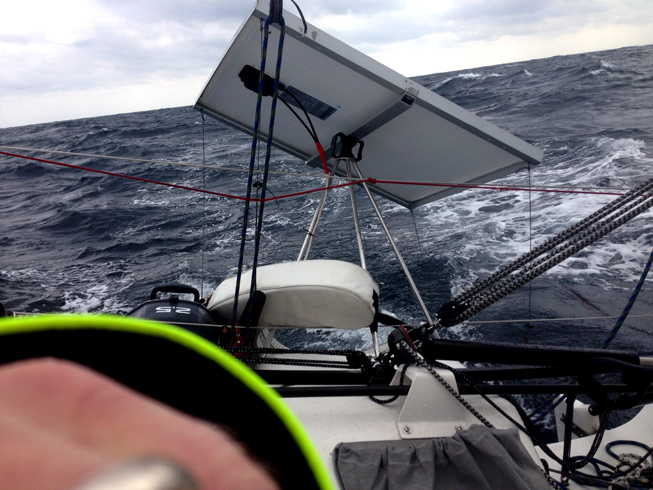

- Install flexible solar panels on deck to reduce need to recharge via diesel engine.

- Install the comfort package: 12v fans and refrigeration, likely SeaFrost.

- Install second mast track in carbon mast to accommodate storm trysail.

- Add a splash of the color to the topsides--by GT3 Creative.

SEASON 1 (2018)

As I sit on my couch in the dead-cold of winter, I'm perhaps contemplating an overly ambitious, some would say, bigly, season. With the goal of mainly cruising the J/120 with family and friends, here's what I've devised for more targeted adventures:

Cruising:

- Early April delivery from Bristol, RI to Larchmont, NY.

- Weekend liveaboards in Larchmont Harbor with Charlie, the reluctant #boatdog.

- Sailing to Newport in May for the VOR stopover.

- Cruising Newport, Block Island, Martha's Vineyard, and Montauk while my 8-year-olds are in camp for six weeks.

- Sailing to Shelter Island, NY in August to moor in Coecles Harbor Marina for a week. At least one day trip to Montauk Lake and back.

Racing:

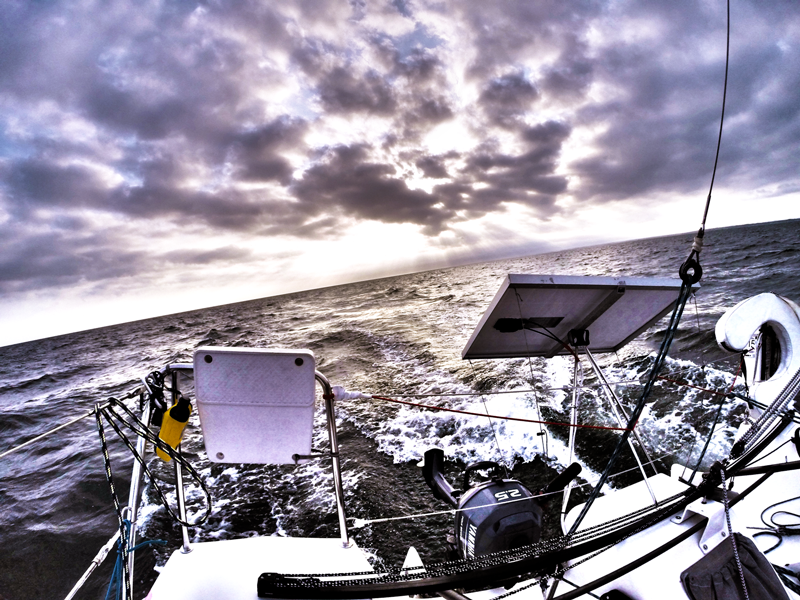

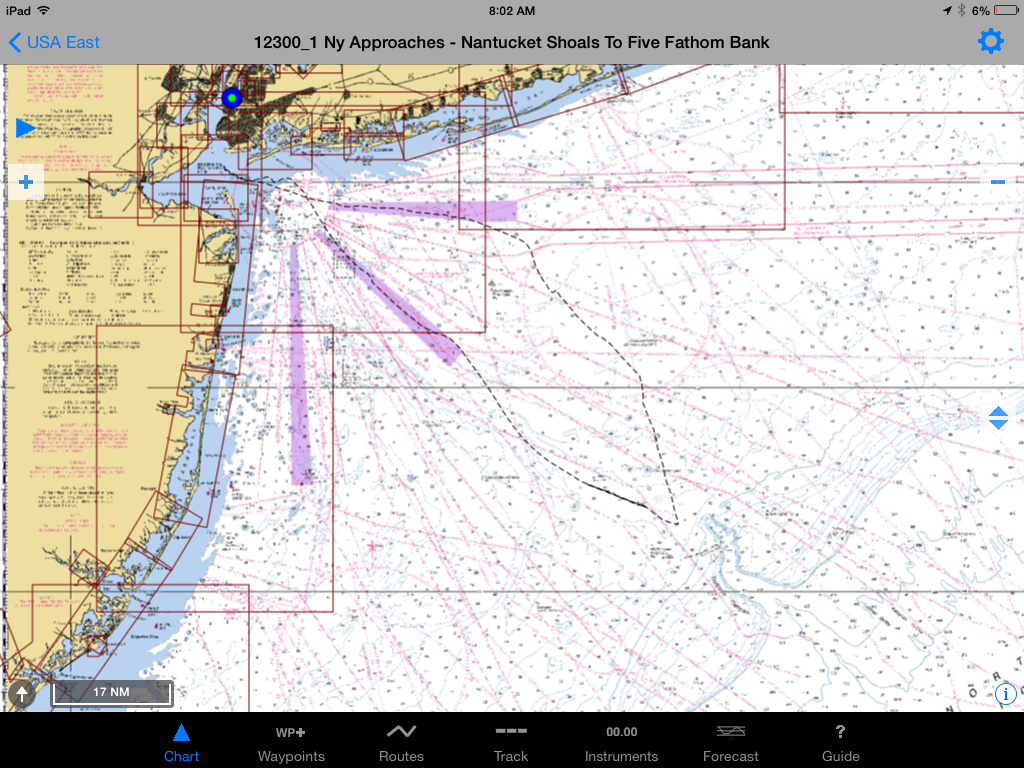

- Offshore 160 - singlehanded regatta hosted by the Newport Yacht Club on July 13, which will also serve as the qualifier for the 2019 Bermuda 1-2.

- Vineyard Race - 4-person, long course.

SEASON 2 (2019)

- Bermuda 1-2. I need to stop talking about this race, and just do it. Plain and simple. June 8, 2019 start. Be there.

season 3 (2020)

- Advanced cruising with Sara and, preferably, the little ladies, perhaps to the jagged coast of Maine. By then, both Sara and the girls better be ready to stand the 12-3 AM watch.

- Sprinkled 4-person racing, maybe a legitimate, double-handed Newport Bermuda Race, who knows!

2018 and 2019 will be interesting particularly because these are big years for my buddy and his Marten 49. And I intend to do all I can to help him achieve his sailing goals. In 2018, that means a class win in the biennial Newport Bermuda Race scheduled for June 15. In 2019, we're shooting to have the Marten 49 on the starting line of the Caribbean 600 and then enter the boat in a "race week" regatta like Les Voiles de Saint Barth.

Did I mention I also work?

Thinking about and planning sailing adventures without the complication of restraint is itself an easy, if not exhausting, task given that it is mostly a hypothetical endeavor. Finding a workable solution toe bridge the gap between sailing goals and sailing action, however, will require disciple and logistical ingenuity to ensure that my goals do not suffer the fate of the underpants gnomes, who failed to identify a workable Phase 2 in their 3-phase plan to reap profits from collecting underpants.

So the planning continues. With inspiration from Warrior Won and Christopher Dragon--and all who made their adventures possible--I'm hopeful that the winter's dreariness will not seize the gears of my own forethought and that I'll be able to identify a logistically sound "Phase 2."

See you out on the water.